by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks

This past Shabbat we read the parsha of Chukkat with its almost incomprehensible commandment of the red heifer whose mixed with “living water” purified those who had been in contact with death so that they could enter the Mishkan, symbolic home of the glory of God. Almost incomprehensible but not entirely so.

The mitzvah of the parah adumah, the red heifer, was a protest against the religions of the ancient world that glorified death. Death for the Egyptians was the realm of the spirits and the gods. The pyramids were places where, it was believed, the spirit of the dead Pharaoh ascended to heaven and joined the immortals.

The single most striking thing about the Torah and Tanakh in general is its almost total silence on life after death. We believe in it profoundly. We believe in olam haba (the world to come), Gan Eden (paradise), and techiyat hametim (the resurrection of the dead). Yet Tanakh speaks about these things only sparingly and by allusion. Why so?

Because too intense a focus on heaven is capable of justifying every kind of evil on earth. There was a time when Jews were burned at the stake, so their murderers said, in order to save their immortal souls. Every injustice on earth, every act of violence, even suicide bombings, can be theoretically defended on the grounds that true justice is reserved for life after death.

Against this Judaism protests with every sinew of its soul, every fibre of its faith. Life is sacred. Death defiles. God is the God of life to be found only by consecrating life. Even King David was told by God that he would not be permitted to build the Temple because dam larov shafachta, “you have shed much blood.”

Judaism is supremely a religion of life. That is the logic of the Torah’s principle that those who have had even the slightest contact with death need purification before they may enter sacred space. The parah adumah, the rite of the red heifer, delivered this message in the most dramatic possible way. It said, in effect, that everything that lives – even a heifer that never bore the yoke, even red, the colour of blood which is the symbol of life – may one day turn to ash, but that ash must be dissolved in the waters of life. God lives in life. God must never be associated with death.

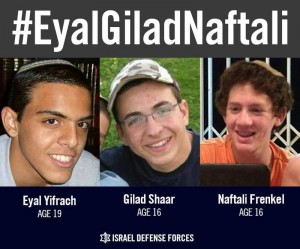

Eyal, Gilad and Naftali were killed by people who believed in death. Too often in the past Jews were victims of people who practised hate in the name of the God of love, cruelty in the name of the God of compassion, and murder in the name of the God of life. It is shocking to the very depths of humanity that this still continues to this day.

Never was there a more pointed contrast than, on the one hand, these young men who dedicated their lives to study and to peace, and on the other the revelation that other young men, even from Europe, have become radicalised into violence in the name of God and are now committing murder in His name. That is the difference between a culture of life and one of death, and this has become the battle of our time, not only in Israel but in Syria, in Iraq, in Nigeria and elsewhere. Whole societies are being torn to shreds by people practising violence in the name of God.

Against this we must never forget the simple truth that those who begin by practising violence against their enemies end by committing it against their fellow believers. The verdict of history is that cultures that worship death, die, while those that sanctify life, live on. That is why Judaism survives while the great empires that sought its destruction were themselves destroyed.

Our tears go out to the families of Eyal, Gilad and Naftali. We are with them in grief. We will neither forget the young victims nor what they lived for: the right that everyone on earth should enjoy, to live a life of faith without fear.

Bila hamavet lanetzach: “May He destroy death forever, and may the Lord God wipe away the tears from all faces.” May the God of life, in whose image we are, teach all humanity to serve Him by sanctifying life.