Walter and his wife Herta have been respected members of the Bournemouth Jewish Community for many years. In his teenage years Walter experienced the horrors of the events leading up to the 2nd World War and lost his parents and sister in Auschwitz. Nowadays Walter is a tireless campaigner for keeping the flame of Holocaust Remembrance alive by visiting schools and educating school children about the horrors of racism and anti-Semitism. This is the life story of Walter Kammerling.

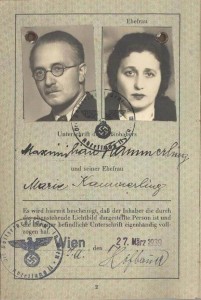

Walter was born in Vienna in 1923. He had two elder siblings, Erica and Ruthi. Walter’s parents, Maximilian and Marie, were very hard working but the family never had much money.

The events that shaped Walter’s life were soon underway. In 1933 Hitler, who was also born inAustria, had become the Chancellor of Germany. Since 1934 Austria was ruled by the conservative, “Vaterlaendische Front” (Patriotic Front) party and was coming under pressure from Germany to join the ‘Reich’. Although the Austrian government was authoritarian and undemocratic, it resisted the attempts by Germany to be annexed. The Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss, who had banned the Austrian Nazi Party, was murdered by the Nazis in July 1934 during a failed coup attempt and Kurt Schuschnigg became chancellor.

Schuschnigg tried to keep Austria independent, he was opposed to Hitler’s ambitions to absorb Austria into the Third Reich, but the pressure both from internal and external elements was growing. Finally, it was decided to hold a referendum on Sunday, 13 March 1938 so that the electorate could vote on Austrian independence.

In 1938 Vienna had a population of 2 million, 10% of which was Jewish. The Jews had been part of the Viennese society for many generations, and were totally integrated. At the time of the referendum Walter was fourteen and describes himself as a rather ‘immature’ fourteen. In the days leading up to the referendum, he remembers a discussion between his father and a neighbour and recalls being frightened when the neighbour said that Hitler would never allow the referendum to go ahead.

Walter does not remember that the referendum was much discussed at home. In the days leading up to the referendumViennawas caught up in an election fever. Schuschnigg made contact with the illegal Socialists and the Trade Unions. Slogans were painted on house walls and pavements. Even schools were targeted, Walter remembers several visits from youngsters stressing the importance to say “Yes” at the referendum. Even though the school children were too young to vote, they still had these visits and it continued right until the Friday before the vote.

At 8.00 pm on Friday 11th, Schuschnigg addressed the nation on the radio and informing them that he had received an ultimatum from Hitler, either to agree to an annexation or there would be war. Schuschnigg wanted to avoid bloodshed and had agreed to give in to the treats. He finished his broadcast with the words “God protect Austria”. As soon as he had finished his broadcast, the streets erupted to the sounds of cheering and shouting. The illegal Nazi party of Austria must have been informed and they were ready.

The violence and terror against the Jews started immediately; They became outlaws overnight, in the truest sense of the word. Anybody could do anything they wanted against the Jews and there was absolutely no protection. The Jews were banned from using public baths, libraries or any closed park. On park benches notices were painted “Forbidden for Jews”. Jewish teachers were immediately dismissed. Jewish property, such as flats, factories, shops, department stores, businesses etc were ‘aryanised’. Sometimes the new ‘owner’ of the property might sign something resembling a contract and pay a small sum towards it; In the case of a paper mill, the amount paid was insufficient to buy a train ticket to the border. Sometimes the Jewish owners of flats were told they had two hours to vacate the flat leaving everything behind. In the beginning of 1938 there were 70,000 Jewish flats inViennaand by the end of that year the figure was down to 26,000 flats.

Following Austria’s annexation, which is known as Anschluss, one of the first things the residents noticed was the scrubbing of the slogans that had been painted on the walls and pavements. The Jews were apprehended and were made to scrub the streets. This was great fun for the onlookers. Walter remembers that walking to school, about a 15 minute walk, was almost like running the gauntlet, as hordes of storm troopers , thugs wearing brown-shirted, and Hitler youths roamed the streets. He would try to walk as inconspicuously as possible, not too fast, and not too slow. When he heard screams and shouting behind him, when Jews were beaten or taken away for scrubbing, he did not dare to look round for fear of becoming one of them.

For the most part Walter managed to avoid this fate but once they caught him and he too was made to scrub the streets ofVienna. The young man in charge, he could not have been older than 17, was not in uniform, he only had the armband of the Hitler Youth. He would not allow them to kneel, but they had to be in a crouching position. When an old man next to Walter fell over, he was kicked and verbally abused. When Walter looked up he could see that most of the onlookers had a smile on their faces. One lady at the rear had a little girl with her; She held her up so that she could also see what was happening and they both smiled. We can only imagine how hard it must have been for the Jews to be mocked in this way by the non-Jewish citizens they had lived side-by-side for generations.

In those days, each of the 21 districts in Vienna had a grammar school ‘Realgymnasium’ and Walter was in RG2, the one in the 2nd district. This was the district with a large Jewish population. At first the non-Jewish pupils were separated from the Jewish ones. They were then moved to schools in other districts and Jewish pupils from other districts came to Walter’s school as that school had been designated as ‘Jewish only’. As a sign of how fast the events moved, by the summer of 1938 they had to leave school.

It was very hard to obtain visas to leave Austria and Walter’s father had tried everything. One day he came home and announced that he had been successful to get visas for them to go to Columbia. He remembers how excited they had been and how his parents had started packing; Unfortunately it turned out to be false hope since the embassy official had sold visas that were not valid.

In October 1938 the Germans expelled Jews with Polish nationality from Austria and left them for days in no-man’s-land under terrible conditions. One such man contacted his son in Paris as soon as he came to Warsaw to tell him about their experiences. His 17 year old son, Hershel Grynszpan went to the German Embassy and shot a diplomat called Ernst vom Rath. On the 9 November vom Rath died and it seemed as if Goebbels had been waiting for this, because all over Germany and Austria Synagogues and Jewish property were set alight. Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps. Somebody, not in uniform, came to arrest Walter’s father. His father had had his first angina attack and was in bed. The man looked at the prescription and, as their doctor was non-Jewish, he accepted it. He took, however, Walter’s sisters to scrub the floors of the local party office that had been a large Jewish flat. Walter’s family lived in a two room flat and Walter was in the other room, but I could still watch them from behind the curtain. Years later Walter asked Erika, who had come to Britain on a domestic permit, about this incident but she just shook her head and did not reply. All 95 Synagogues and prayer houses in Vienna were utterly destroyed except one, which housed the archives of the Jewish community. The fire engines did come out but only to protect the properties adjacent to the Jewish property on fire.

The Nazis called that night ‘Kristallnacht’. Walter does not like to use this name for the terrible events of that night because it sounds rather romantic but it was a night of unimaginable horror for the Jews of the Third Reich.

All this happened when the world was ‘at peace’; There were foreign journalists in Germany and Austria and they all observed and reported what had happened. To the credit of Great Britain only 11 days after that infamous event, on 21 November, the Parliament discussed these troubling developments and decided to allow 10,000 Jewish children to be permitted to come to Britain unaccompanied by their families. This decision saved the lives of 10,000 children. A deposit of £50 was required to ensure that the refugees did not become a burden on the country. The money was collected and from the beginning of December 1938 Jewish youngsters started to arrive in Britain on the ‘Kindertransport’. Walter does not know what his parents had to do but I was told that he would be going to England.

Walter was a typical 15 year old and I don’t remember asked any questions. He remembers saying goodbye to his father who was in the Jewish Hospital with angina; His father was in tears and Walter had never before seen him cry. Walter was choked and did not want to leave his bedside. An older cousin who was with Walter just took him by the hand and led him away. Walter stood at the door and looked back; It did not cross his mind that this could be the last time he would see his father. Later that night his mother and sisters saw him off at the station. Walter was almost in a daze; He remembers seeing his mother, Erika and Ruthi on the platform from the window of his train carriage.

When Walter left Vienna his father was 48 years old, his mother 44 and my sisters 18 and 17 years old. Ruthi was just too old to come on a Kindertransport, for which the cut-off age was 16. That was the day that Walter saw his parents and his sister Ruthi for the very last time. He was not aware at that time, that Britain had saved his life for which he is extremely grateful to this day.

Walter and his fellow travellers landed in Harwich on Monday, 12 December 1938 and were taken to a holiday camp; He thinks it was a Warner’s holiday camp, which was used to house the children. It was in the camp, a few days later, that Walter craved to talk to his mother and realized that she was no longer ‘next door’. Of course he sent letters home, but writing home was just another new experience. He remembers seeing couples come to the camp to choose the children they would like to look after.

In January 1939 Walter and three other boys, all about the same age, were sent to Northern Ireland. The Jewish community in Belfast looked after them. At first they were taken to a hostel in Clifton Park Avenue and after a short time there, they were sent to farm in Millisle, Co. Down, which the ‘Jewish Committee’ secured for them. Again, the help and care they experienced in Northern Ireland was another life saver. There were different groups on the farm; The ‘adults’, around 20 middle aged and old refugees from Austria and Germany; the ‘Chalutzim’, youngsters in their twenties, belonging to an orthodox Zionist organisation, who used the agricultural experience as training for their forthcoming aliyah to Palestine – actually some of them went on to become co-founders of Kibbutz Lavi; and then there was the third group consisting of the ‘children’, most of whom had come on Kindertransport.

They could still correspond with their families, right up to the outbreak of the war on 3 September 1939. Walter’s sister Erika managed to obtain a domestic permit to come to Britain and she arrived here on 4 July. Ruthi, who was only being 17, was too young to get a domestic permit and had to stay in Vienna. Walter stayed on the farm until the summer of 1942, when he managed to get a job in Carshalton, London Borough of Sutton. When he came back from Northern Ireland he saw Erika again after nearly 4 years. Walter hoped that they could live together, but Erica worked in a hotel and had to sleep there.

Later that year Walter managed to find a job in a munitions factory inLondon. He found a room not far from the factory, but the landlady expected him to turn up the same day and Walter arrived after work the following day by which time the room was taken. A fellow refugee in the factory told Walter about a ‘War Workers’ Hostel’ at Swiss Cottage. It was a hostel run by the Austrian Centre, a group of Austrian refugees that tried to organise its members to do everything for the war effort, to beat the National Socialists and to establish a free, democratic Austria after the war. Walter was very glad to be accepted there and subsequently joined the Youth Organisation ‘Young Austria’, which is where he met his future wife Herta.

When in the summer of 1943 parliament decided that ‘enemy aliens’ could join the forces and carry arms many of the ‘Young Austrians’ volunteered to join the forces. In March 1944 Walter was called up and joined the Suffolk Regiment. In November he had ‘embarkation leave’ when Herta took him to meet her parents in Salisbury. Herta, who was also from Vienna, had arrived in Britain on a Kindertransport with her brother Otto on January 12 1939, when she had been 12 and Otto 8 years old. Her second brother Eric was borne the day Herta and Otto arrived in Britain. Her parents managed to get a domestic permit and came to Britain shortly before the outbreak of the war. Walter managed to convince Herta to get married on a special permit and they did. Herta was still under age but Walter was lucky to have had his 21st birthday two weeks before. This was the best thing that had happened to him. In December 1944 Walter first travelled to Belgium and then to Holland with this regiment.

After the war, they were given the chance by the army to be ‘repatriated’; They took it and went back to Austria. Britain had offered them shelter when they needed it most and now it was time to go back and find out what had happened to his family. They also thought that they could help to build a new Austria, like young people do. In the event he could not find any of his family.

Walter tried to catch up with his studies, took a matriculation course and enrolled at the Technical University. As he had to work to support his young family, he became a “Werkstudent”. It was an extremely difficult time and Walter managed to cover half of a five-year course in 10 years. Both their sons were born in Vienna. The births of their sons Peter in 1948 and Max in 1955 were the highlights of their life. They are very proud of their sons, their five grandsons and their great-granddaughter

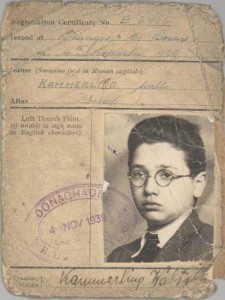

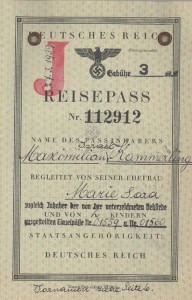

Walter found a box his father had left with non-Jewish friends when they were sent to Theresienstadt, a concentration camp near Prague. The box contained his family’s passports, documents and books. He also found postcards his parents had sent to non-Jewish friends in Vienna who had sent them food parcels. The last card his father sent was dated 2 Sept 1944, in which his father wrote that Ruthi had married Ernest on 25 June 1944.

A friend of Walter’s, whom he had known since his Kindergarten days, gave him a book called ‘Totenbuch Theresienstadt’ (means Book of the Dead Theresienstadt) which lists all the names of the persons sent to Theresienstadt from Vienna and where they were sent to from there. Walter found the names of his family in that book and found out that they had been deported to Theresienstadt in September 1942. Walter’s father and Ernest, the brother-in-law he never knew, were subsequently deported to Auschwitz on 29 September 1944. His mother and Ruthi left Theresienstadt on the penultimate transport to Auschwitz on 23 October. Two days after leaving Theresienstadt his family was murdered; His father Max was 54, his mother Marie 50 and his sister Ruthi not quite 23 years old. In November 1944 the gas chambers of Auschwitz stopped working.

In subsequent years, Walter did experience latent and sometimes not so latent anti-Semitism. He worked in the design offices of AEG, and one day two of his ‘colleagues’ were speaking about another Jewish man working in another department; Making sure that he could hear it, one said to the other “There is another one who fell through the grate” referring to the crematoria in the concentration camps. After 11 years in Austria Walter and his family decided to come back to Britain. Both Walter and Herta had had their formative years in Britain and felt more at home here than in Vienna. They had known Vienna as children and had loved its sounds, smells and sights but it also carried too many unpleasant memories. The Austrians had regarded the Allied Forces not as liberators but as occupiers and anti-Semitism was certainly not dead.

As Herta’s parents lived in Bournemouth, Walter and his family settled in Bournemouth in 1957. Despite the terrible events of his teenage years Walter considers himself to be very lucky to have found a home here in Bournemouth and to have married Herta to raise a lovely family. They have been very happy despite all the struggles and they have a wonderful family.

Walter is regularly invited to speak in local schools about the Holocaust; He was contacted by the Holocaust Educational Trust to talk to schools further afield and has been to Durham University and Newcastle. We wish Walter, Herta and their family many more years together.

M. Ozdamar